This edition of a teacher blog post is courtesy of Calypso Harmon’s 8th grade science classroom in California, and how she incorporated hands-on learning during her students’ astronomy unit.

It was time to start teaching astronomy, and I remembered that I read a great article last year in the March 2017 issue of Science Scope. I pulled it out an re-read it, and the article really inspired me to start the unit differently this year. On the first day, I introduced the lesson by talking about an experience the science teacher in the article had: she was looking out at the setting sun, and she could see a crescent moon, Jupiter, and Venus all in the sky at once.

It was time to start teaching astronomy, and I remembered that I read a great article last year in the March 2017 issue of Science Scope. I pulled it out an re-read it, and the article really inspired me to start the unit differently this year. On the first day, I introduced the lesson by talking about an experience the science teacher in the article had: she was looking out at the setting sun, and she could see a crescent moon, Jupiter, and Venus all in the sky at once.

My challenge to my students was: Is this even possible? Make a model to show if this could really happen, or if it is impossible.

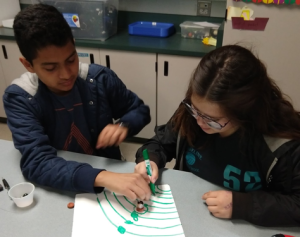

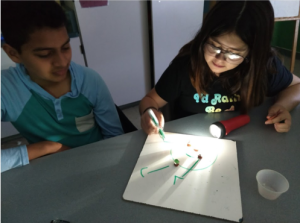

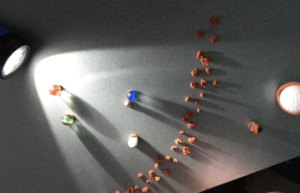

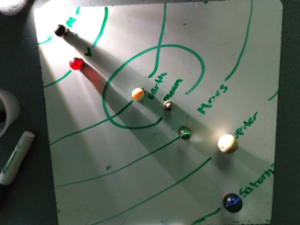

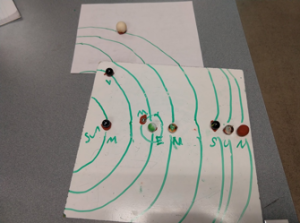

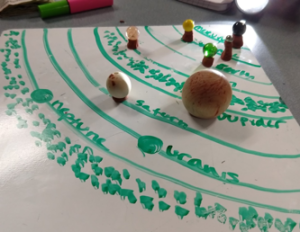

Students had a flashlight to represent the sun, marbles and balls of different sizes to represent the planets and moon, and a whiteboard to help identify the objects and indicate their paths. I expected these initial models might be pretty far off, but as the class progress, I realized many of my students had a lot less background knowledge of the solar system than I expected. Although some knew that Venus was closer to the sun than Earth, and Jupiter is further away, many students were not sure what order to place the planets. Most knew the planets orbit the sun, but not everyone. And when prompted to show the path the moon would take, one group of students were not sure if the moon moves at all. I have to admit, I was a bit shocked, but I’m so glad I began with this activity because it was a great way for me to assess where they are starting from. After they made their models I had them write in their notebooks to explain whether or not they thought the teacher really could have seen that or if she misidentified one or both of the planets. Then they shared their writing and thinking with a classmate from a different group. Finally students completed a short reflect on how well their group members functioned as a team.

After a couple of days of some instruction in the basics, the groups tried again. This time their models were more detailed and more accurate. Some groups got added paper to be able to extend the orbit of Jupiter, to show how they could all three could be visible from Earth.

I’m very excited about how this sequence of lessons has unfolded because of the way it really engaging students and required them to do more than just memorize. They were thinking critically, arguing to support their points, using the model to show evidence to support their thinking, considering different ways of looking at things, and practicing working collaboratively. I felt like their understanding really grew, and their interest and curiosity was sparked by starting this unit with a question.