Bridget Heneghan is a science teacher in Chicago, and is participating in Letters to a Pre-Scientist for the second year. Here, she discusses the importance of her students being able to relate to scientists and see themselves pursuing those same careers.

Since my very first year of teaching, the most noticeable thing in my classroom has been big black letters on my wall pronouncing: “I HAVE NO SPECIAL TALENTS. I AM ONLY PASSIONATELY CURIOUS.” Next to the letters is the infamous picture of the famous speaker, Albert Einstein, whom the students and I just refer to affectionately as “Al.” In school, we spend a lot of time teaching important knowledge and ways of thinking passed down to us from these amazing scientists, but it is hard for the students to understand that these wise, wonderful scientists are, well, people. Many kids go through their school career imagining these scientists mixing up “potions” and various unnamed chemicals in laboratories and graduate with a very limited understanding of what a scientist is or does. This is my second year in the Letters to a Pre-Scientist program, and one of the most important things that LPS has done for my students is letting students see the people behind the curtain, letting them understand that scientists are people just like them

I teach at Hibbard Elementary School, a public school in Chicago. We are a larger school, housing over 900 students in just preschool through sixth grade, and about 94% of our students are labeled  as low-income. We are located in the Albany Park neighborhood, which is well-known for its diversity and being a gateway for many immigrants coming to the city. More than half of our students are “limited English proficient” and come from a wide array of backgrounds. In my class, I have students who speak languages including (but not limited to) Malay, Arabic, Swahili, Romanian, and Spanish. We have students who have lived in Albany Park for their whole lives, students who moved here from Ecuador three years ago, and students who came as refugees from war-torn countries a few months ago.

as low-income. We are located in the Albany Park neighborhood, which is well-known for its diversity and being a gateway for many immigrants coming to the city. More than half of our students are “limited English proficient” and come from a wide array of backgrounds. In my class, I have students who speak languages including (but not limited to) Malay, Arabic, Swahili, Romanian, and Spanish. We have students who have lived in Albany Park for their whole lives, students who moved here from Ecuador three years ago, and students who came as refugees from war-torn countries a few months ago.

It is important that my students are able to see themselves as future scientists. One way that I include this in my instruction is by reading picture book biographies to my students throughout the year. I have spent a lot of time researching and finding biographies to read in my class that detail the lives of scientists that are related to our earth science content. I have been intentional about including diverse scientists to represent my diverse population, but, unfortunately, that specific genre (diverse-scientist-picture-book-biographies-related-to-earth-science) is a limited one. We spend time reading these stories as a class, and then students identify character traits to describe the scientist using text evidence. We come to a consensus on the most important traits and then we make a word web connecting all of the scientists that we read about over the year.

The students use the web to make connections not just about what scientists do, but what kind of people scientists are. One of my favorite things that a student ever said in my classroom was, “Well, of course she was hardworking and creative! She was a scientist!” Students really start to see that scientists are more than just their lists of accomplishments: they are curious, hardworking, persistent, and they care deeply about what they do. At the end of the year, they write a picture book for kindergarteners describing what it means to be a scientist using the character traits that they have observed in all of the biographies we have read.

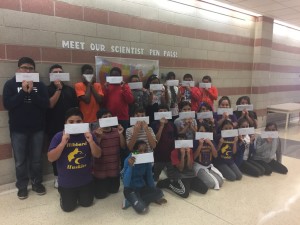

Letters to a Pre-Scientist added so much more dimension to my students’ understanding of what it means to be a scientist. Scientists also happen to be funny, interesting, and relatable. They make my students laugh, make them gasp and cheer on letter opening day, make them hug their letters, and make them reach across the table talking over all of their friends saying what “my scientist” did for the last month. One of my favorite letters from last year was one of my sixth graders writing to a tenured professor telling her, “You shouldn’t give up that easy, you should try and be the best because I believe you did good on playing the piano and I know you will be better at playing the guitar.” These scientists are their friends and supporters, and our students are ready and willing to return the favor. Because, of course, my students have learned that scientists––and pre-scientists––are hardworking and creative and “passionately curious;” but they are also passionately kind.